On Thursday, October 12, 2017, Stephanie Boluk (University of California, Davis) delivered a lecture titled “From Metagames to Moneygames.” This follow-up interview with Boluk and Patrick LeMieux, co-authors of Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames, was conducted by Rebecca Cheong and John Seabloom-Dunne, graduate students in the Department of English, by email during spring and summer 2018.

In the book we write “prepositions are to parts of speech as metagames are to games: they anchor games in a time and place” (11) but we could also say it a different way: history matters, context matters, play matters.

RC and JSD: Metagaming, as a scholarly project, takes up the oft-discussed radical and subversive potential of games as a critical apparatus within the context of their present use. In the introduction, you locate this potential “in, on, around, through, before, during, and after” videogames as a historical practice rather than the relatively common emphasis that scholars place on a future “speculative horizon” (4). Is there a disciplinary risk to this investment in the present, and what purchase might its wide adoption find on the particular domain of Game Studies and the broader field of the humanities? Does the idea of “the metagame” help anchor this present focus?

Also, although the book is a scholarly one and situated within a scholarly domain (in its approach to its topic, its delivery of arguments, etc.) it is also anti-disciplinary in a sense, insofar as it doesn’t make concrete conceptual distinctions, or at least there isn’t a clear zone of distinction you have carved out between metagame and game. In some ways, you appear to resist the reification of video games as object. Writing a scholarly book with an anti-disciplinary disposition seems to be a risky move. It begs the question of what is at stake for this project in the scholarly world. How would you position the book within the discipline of game studies or the broader humanities, and what are some disciplinary risks a study like this one faces in the present?

SB and PL: First of all, thank you for the interview! Metagaming has been out for about a year in print as well as online at University of Minnesota’s new Manifold open access publication platform where we’re continuing to update the software and add video figures. It’s exciting to get a chance to reflect a bit on the project with you!

There’s a lot to unpack here but Metagaming begins with a simple question: what do players mean when they say metagame? This word pops up again and again in live commentary and forum discussions around speedrunning, esports, competitive fighting games, massively multiplayer online games, and virtual economies as well as in conversations around collectible card games, tabletop role-playing games, and board games. So we started by wondering if metagame referred to a specific technique, a historical practice, a personal preference, a community culture, or just play in general? Does it mean the same thing across different gaming discourses or is it dependent on context? Is it a productive lens for thinking about videogames or does it pose a challenge to the ways we talk about technical media? And the answer is, as you might imagine, a bit of all the above.

After considering both the longer history of the term—from its etymology as a kind of ur preposition in Ancient Greece to Nigel Howard’s cold-war game theories attempting to solve the Prisoner’s Dilemma in the 1970s to Richard Garfield’s game design philosophy for Magic: The Gathering in the 1990s to its increasing use within the streaming services, social media platforms, and digital storefronts that attend videogames in the 2000s—we found that the word metagame itself operates like a kind of language game. Broadly speaking, metagaming is both a general signifier for the things happening in, on, around, and through games in general as well as a mark of how specific people play a specific game in a specific place at a specific time. It’s both a diffuse category of attitudes, experiences, relationships, and exchanges related to games as well as a precise articulation of how we play. In the book we write “prepositions are to parts of speech as metagames are to games: they anchor games in a time and place” (11) but we could also say it a different way: history matters, context matters, play matters. We find the things people do with videogames are often more suprising, inspiring, and troubling than when imagining the game as an isolated object and whenever we write about a given game we always try to include who (or what) is playing. If you are talking about games and are not naming specific players, something is probably wrong! So we started exploring the diverse array of things—some good, some bad, and many we are ambivalent towards—that happen when we play with videogames.

What is at stake is precisely the history, materiality, embodiment, and economies of play that a more narrowly focused study of software, code, platform, and object might overlook.

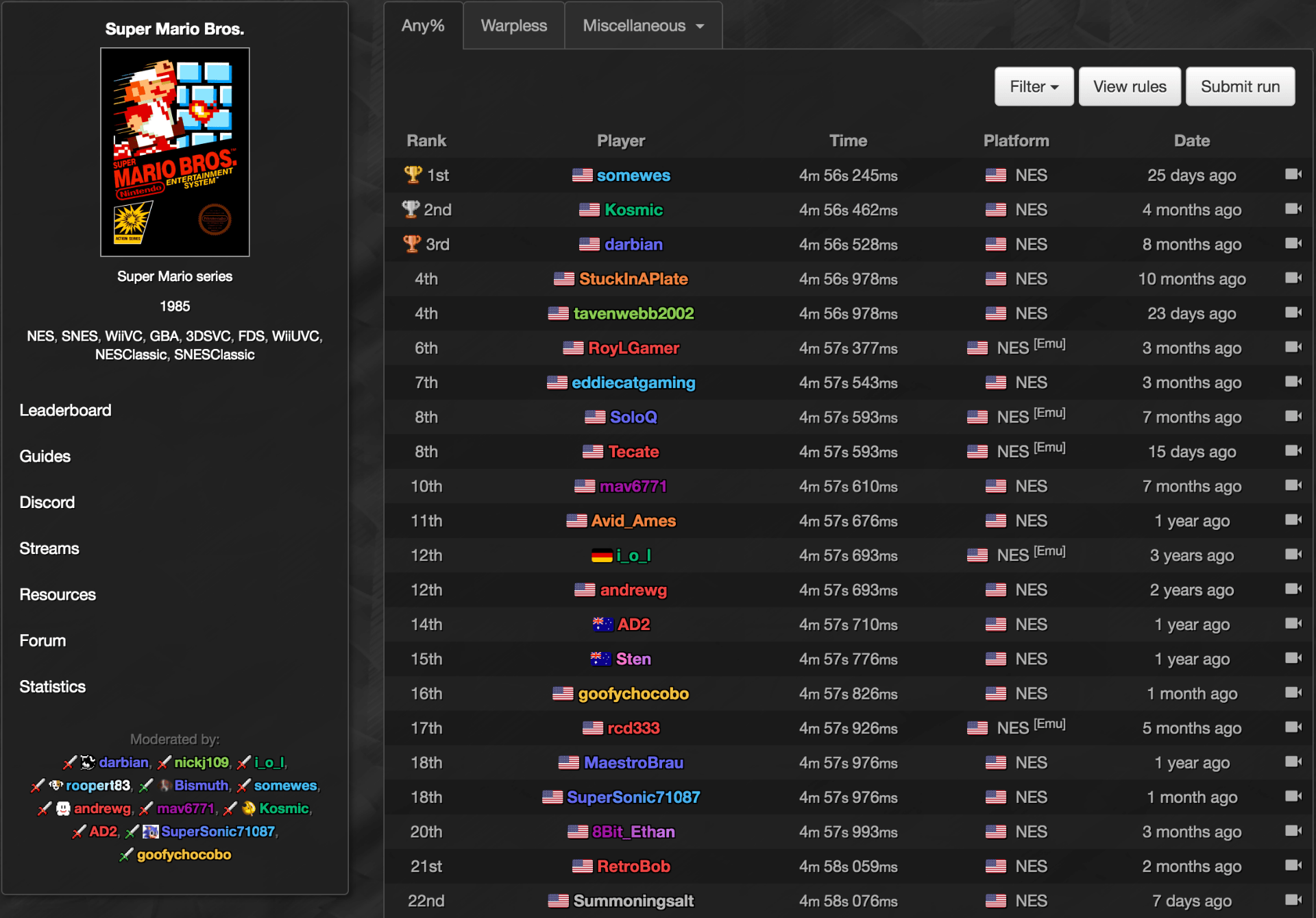

As such, Metagaming participates in a disciplinary shift from imagining games as encapsulated technical objects to a consideration of the diverse things people do with games (a shift that includes new work by scholars like Adrian Shaw, Bonnie Ruberg, Brendan Keogh, Darshana Jayemanne, Aubrey Anable, and many others). To speak directly to your question, this is not necessarily a presentist approach focused on the now, but, following the work of expert players like Narcissa Wright, Richard Terrell, and Dan Stemkoski, we offer a way to document and delve into traces of play. And as anyone working on speedrunning can tell you, the present always changes! New techniques are discovered, new categories of play are invented, and old records are broken. In fact, while copyediting the book, we had to return to every discussion of world records to historicize them because they had all been beaten while we were writing! In Metagaming we’re explicitly interested in what this kind of media studies methodology—in which we perform a medium specific analysis of the evidence of play—reveals about technology and culture in the 21st century.

But you’re right that Metagaming was also responding to a specific conversation occurring in game studies around the potential of games and play to produce political change. Although the book engages philosophical accounts of games and play occurring in other disciplines like anthropology, sociology, and history (i.e., Huizinga, Caillois, and Suits) as well as some of the first books dedicated to the study of videogames and culture (i.e., Aarseth, Juul, Ryan) the work of many theorists and designers in the mid-2000s imagined the critical, political, and material implications of videogames. Books like Gaming by Alexander Galloway, Gamer Theory by McKenzie Wark, Critical Play by Mary Flanagan, and Games of Empire by Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter all emerged around the same time (and were deeply influential to us in graduate school). One thing we noticed in that moment was the ways in which these projects imagined a future where games produce cultural change. For its part, Metagaming begins by looking back to the work of player communities in order to find evidence of the radical potential promised in these books.

What is at stake is precisely the history, materiality, embodiment, and economies of play that a more narrowly focused study of software, code, platform, and object might overlook. We wanted to find a way to talk about what games do, not just what they are. And to think about play in this way we found ourselves investing in the work of scholars like Lisa Nakamura, T.L. Taylor, James Newman, Henry Lowood, Raiford Guins, Doug Wilson, and Laine Nooney whose research methods carefully and thoughtfully attend to cultural histories alongside gaming technologies. Ultimately, the point of establishing this contrast is to try to articulate and analyze the phenomenological gap between our embodied experience of technical media and the speed and scale of mechanical, electrical, and computational processes operating outside the register of human consciousness. As we write at the beginning of the book, we think metagames are the “material trace of the discontinuity between the phenomenal experience of play and the mechanics of digital games” (9) and throughout Metagaming we attempt to study these traces in order to come to terms with what we can and can’t know about contemporary technology.

From considerations of anamorphosis and graphics to disability and control, seriality and history, as well as economics and esports, the chapters of Metagaming investigate and intervene on videogames as a paradigmatic site for thinking about our relationship to technical media in the 21st century. And this is why we characterize play as a form of practice. When speedrunners discover an exploit and produce new categories to race they are designing games. When esports teams research their opponents to counter a popular strategy, they are creating new forms of play. In this sense, practice is a primary category for us and is also one of the reasons we wanted to make our own games alongside each chapter. In fact, an early subtitle for the project was “Videogames and the Practice of Play”!

RC and JSD: In the opening chapters of Metagaming, you discuss the presence and popularity of various indie games that, to some extent, fall within Andy Baio’s concise definition of “playable games about games” (29), a definition many people coming to this work for the first time might have. You are careful to expand your own understanding of metagames beyond the characteristics of self-referentiality and remix, but games about games nonetheless still play a role in the framing of this work. Take for instance, your own metagame, 99 Exercises in Play, which draws material from World 1-1 of Super Mario Bros. What do you see as the relationship between these “games about games” and the wider understanding of metagaming that you explore and interrogate?

SB and PL: This is another great example of the flexibility of language! Andy Baio’s use of the word that comes closer to the way humanities scholars talk about metafiction or metafilm than the way the word functions in game theory to discuss strategy and technique don’t immediately seem to speak to one another, but even then we found moments of overlap.

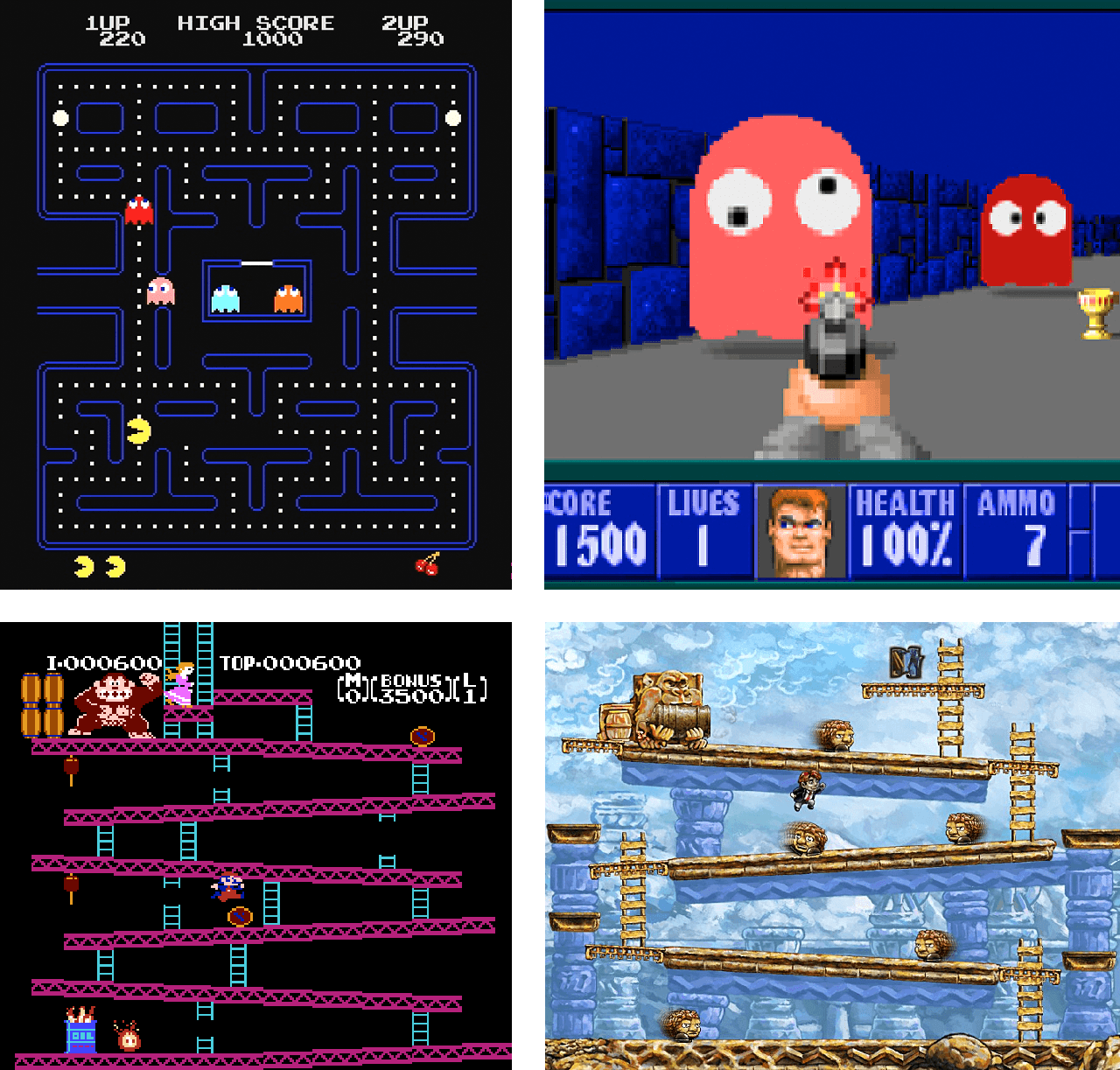

Although the specificities of play are often ephemeral, private, or often overshadowed by the histories and stories of software, even game design can operate at the level of a metagame. Preferences, attitudes, beliefs, and ideologies about play are often captured within videogames themselves. Although franchises like Mega Man or Street Fighter mark time by manipulating a shared codebase or underlying game engine, other games like The Stanley Parable or Kentucky Route Zero make metagames through asset development, level design, or narrative references. We wrote about a few of our favorite examples in Metagaming like John Romero’s bonus levels in Wolfenstein 3D which recall Pac-Man or the Donkey Kong-inspired level of Braid, but if you look for it you’ll start to notice games are often about other games. Ian Bogost summarized this point in a recent article where he wrote “More often than not, games are about the conventions of games and the materials of games—at least in part. Texas Hold ’em is a game made out of Poker. Candy Crush is a game made out of Bejeweled. Gone Home is a game made out of BioShock.”

And, as you mentioned, the definition of metagames as “games about games” aligns with other media genres like metafiction and metafilm. Readers approaching the book from literary or film studies backgrounds might be familiar with this particular kind of play but we found that this meaning is actually the least used by player communities. Usually the metagame refers to a particular strategy, playstyle, preference, or fashion used by specific players at a specific time and place (which is why we focus on the metagame as an index of the history of play.) So speedrunners might use it to refer to the current route or category definitions, whereas esports players might refer to the acronym META: Most Efficient Tactics Available. The original games we designed alongside each chapter of the book attempt to deploy both of these forms of metagaming by bringing together references to specific software while suggesting alternative forms of play.

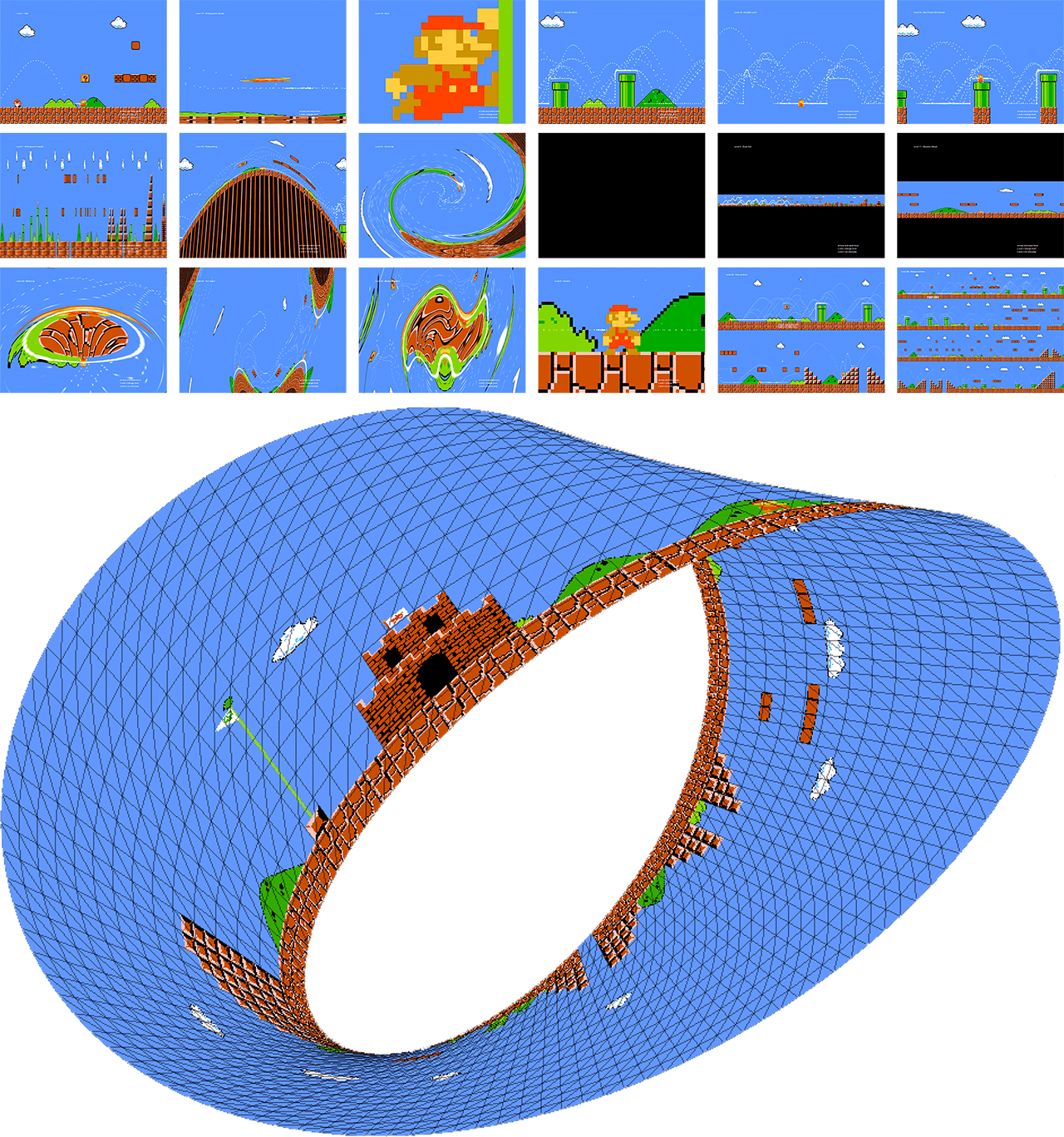

99 Exercises in Play, for example, is a game about Super Mario Bros. in the sense that it attempts to simulate World 1-1 of Miyamoto, Tzuka, Kondo, and Nagako’s game (which turned out to be a much bigger challenge than we initially thought!) Following Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style, our game offers a series of variations in order to imagine the diverse and unexpected ways in which people might have played Mario. Play the game upside down, right to left, in slow motion, sped way up, with a time limit, without touching the ground, with multiple Mario’s, and on and on. We currently have 30 variations in the game and are planning to add the other 69 (as well as enemies and power-ups!) sometime this year. Crucially though, in 99 Exercises in Play we never change the metrics of Mario’s relationship to his environment. If he jumps twice as high, the level also grows twice as tall. We wanted to make sure that the game still bears a resemblance to how people play on the Famicom and Nintendo Entertainment System. It’s like a cookbook featuring different recipes for metagaming Mario while, in the process, revealing the noisy history of World 1-1. Super Mario Bros. is not a throughline from pressing START to the flagpole—it’s a cloud of potential play.

RC and JSD: In chapter 6, during your discussion of Anita Sarkeesian and the harassment that she has experienced, you draw a parallel between Mark Hansen’s idea that media constitute an “environment for life” with metagames’ function as an “environment for play” (276). You pose the question of what happens when this environment becomes increasingly “unliveable.” How does this uninhabitability contribute to the calcification of methods and techniques of play, and what might an understanding of metagaming offer in response?

Additionally, as a final question, if you don’t see the radical creative potential of videogames in the future, what do you see there instead? The final chapters “Turning the Tide” and “Breaking the Metagame,” you consider the rise of “a vectoral regime” where divisions between play and labor are untenable, and the “standard metagame” regiments and restricts diverse forms of play. What place, if any do metagames have in this future?

SB and PL: Whereas the solidification or calcification of a given metagame can occur through the policing of standards and norms (whether via Nintendo and Valve’s corporate strategies of enclosure or the toxic violence of gaming communities), players also constantly resist these forms of control. Communities come and go, audiences ebb and flow, sometimes hibernating for years only to be revived a decade later. The discovery of old forum posts, new technical exploits, new ways of thinking about or engaging with a game, or a new group of people discovering a game can reinvigorate a metagame. Both because and despite attempts at enclosure (like targeted harassment campaigns or cease and desist notices), the metagame moves, migrates, and mutates as players respond to their environments of practice. And although patching software to be more inclusive, accessible, and open is always important, technofixes cannot produce change without broader cultural shifts also occurring. Change the metagame—whether through hiring practices, in-game representations, or fostering more diverse player communities—and you change the game. (And of course the converse of this is also true, which is what we’ve all had to contend with as toxic fandoms and conservative consumer groups actively fight to shore up their borders.)

From idle games and cryptocurrency, virtual economies and grey market gambling, crowdfunding and speculative finance, the financial relationship between sports and esports, and even the tight circuit between entertainment media and US politics, money and games are becoming harder and harder to differentiate.

The practices we describe in Metagaming are both radical as well as reactionary and our next book is starting to look like the Empire Strikes Back as it will focus on some of the darker aspects of playing videogames. It’s tentatively titled Money Games and picks up where Metagaming left off: with the ways in which videogame corporations expropriate and enclose diverse forms of play; the ways in which players commodify their time and attention on social networks like Twitch, YouTube, and Steam; the ways in which money operates not for profit but to signal and measure value (be it in the office or at home); the gamblification of games and larger move from wages to wagers under computational capitalism; the ways in which both virtual economies and finance capital operate according to technical mechanisms of digital media. Here we’re looking at how money functions as a game mechanic and how game mechanics function as money—money as a medium of exchange, a medium of trust, a medium of communication, and, of course, a medium of play. From idle games and cryptocurrency, virtual economies and grey market gambling, crowdfunding and speculative finance, the financial relationship between sports and esports, and even the tight circuit between entertainment media and US politics, money and games are becoming harder and harder to differentiate.

In 2012, game designer and researcher Eric Zimmerman wrote a manifesto declaring that we are living in a “ludic century.” The manifesto makes the bold and hopeful declarations that “there is a need to be playful,” “information has been put to play,” and “gaming literacy can address our problems.” We vividly remember how promising games felt in this moment and how it did indeed seem that they were the ideal expressive medium for dealing with the problems of increasingly abstract, inaccessible, and systemic problems—global warming, financialization, racism, international politics, bureaucracy, and computation itself. Games seemed uniquely positioned as tools for managing complexity. And he wasn’t alone in this utopian rush towards gaming. Zimmerman published this manifesto around the same time as the ethnographer Edward Castronova’s Exodus to the Virtual World and the games researcher Jane McGonigal’s Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. In the early 2010s, buzzwords like gamification were being thrown around in corporate board meetings and game labs were springing up across academia. But after the financial collapse in 2008 and the emergence of a gig economy with Uber, AirBnB, Bird, and WeWork, it seems we’re actually living in an age of precarity where our wage is increasingly a wager and our games are always gambles.

Rather than thinking about how games can counter this logic, we think it’s time to consider how the metagame already influences and impacts daily life and, when necessary, how to stop playing.

Once the dust settled in the second decade of the 21st century, it became clear that the game is rigged. Reality may be broken but it’s the model of a rational, disembodied, ahistorical, meritocratic gamespace that helped get us here. And Zimmerman was totally right! But instead of a Suitsian utopia of fun and games, we got the dystopian version of the Ludic Century. Information has indeed been put to play, but it’s so much so that Trump—a man who made a living from toying with brands, hosting game shows, buying golf courses, and gaming social media—can comfortably dismiss journalism as fake news and alternative facts while promising constituents they’ll “win so much they’ll be tired of winning.” Rather than thinking about how games can counter this logic, we think it’s time to consider how the metagame already influences and impacts daily life and, when necessary, how to stop playing.

Bibliography

Boluk, Stephanie and Patrick LeMieux. 2017. Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN. https://manifold.umn.edu/project/metagaming.

Bogost, Ian. 2017. "Videogames Are Better Without Stories." The Atlantic. April 25. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/04/video-games-stories/524148/.

Zimmerman, Eric and Heather Chaplin. 2013. "Manifesto: The 21st Century Will be Defined by Games." Kotaku. September 9. https://kotaku.com/manifesto-the-21st-century-will-be-defined-by-games-1275355204.